We stopped on a face of sheer rock overlooking the valley. The late fall foliage scorched the base of Mount Monadnock, and a mist filled the gaps. A storm was coming, and the wind was beginning to show its teeth. It would be bitter cold at the top. We sat down to eat our lunch before continuing up, my father and I.

I had graduated from college the previous spring, and I was deep in thought over the meaning of this recreational outing. Was the relationship here still primarily father and son? Or were we now primarily friends, bonded by long familiarity but freed from the hierarchy inevitably bestowed by the differences in physical size and life experience which, when I was younger, were too pronounced to be denied? Surely this was a relationship of mutual respect?

My father was still much larger than I was, though–several inches taller and a hundred pounds heavier. It would always be that way, at least the height. I was thin and light. I jumped over the rocks, like a little kid, while my father lumbered, slow and steady, pausing often to wipe his forehead and, fists on hips, inspect the neighboring trees. Yes, we were physically different, but many men my father’s age were as small and light as I was.

That’s not to say that my father was not young in his way. We ate our chicken salad sandwiches. The wind kicked up and, proud of my foresight, I took a scarf from my bag to bind around my long, exposed neck. Hikers coming down the mountain had said, without being asked, that the wind was easily 60 miles per hour at the summit. My father had scoffed a little at the figure, but now said, “Jesus!” as he ran after a piece of waxed paper which had flown free, then gave it up. “Jesus is right,” I said. “Storm is coming in!”

We began gathering up the remains of the food and sticking it in the backpacks. I was preoccupied with my father’s hands and the way they manipulated the plastic bags and Tupperware containers. He extended an index finger carefully and efficiently and pressed slowly on the button in the middle of the Tupperware lid, just slow enough so that there was some suspense as to when the characteristic pop would be heard. I avoided doing this with my containers, although I smiled to think that I wanted to. I had the presence of mind to also think, “We share a compulsive pleasure in the tactile.” Out loud I said, “Have you closed your lids properly, Dad?”

“Uh, yes, they’re closed, safe and secure. Thanks for asking.”

“Then we can face the mountain.”

I walked behind my father for a while and noticed with amusement and affection the way he kept his index fingers extended as he walked as if constantly pointing at the ground. “Do I walk that way?” I asked myself. No, I didn’t. My hands were fists. I rested one on a stone and looked at it. My own fist.

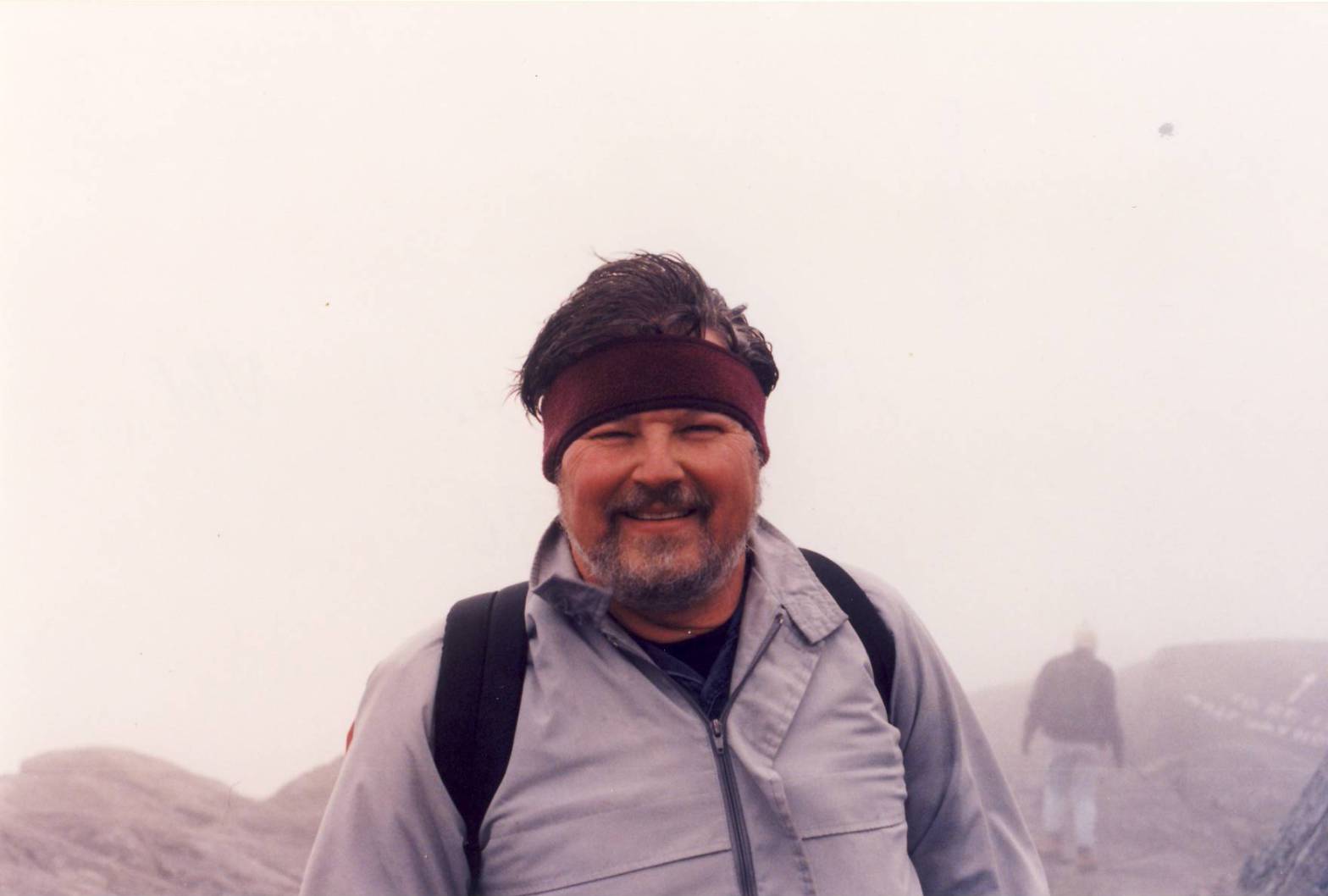

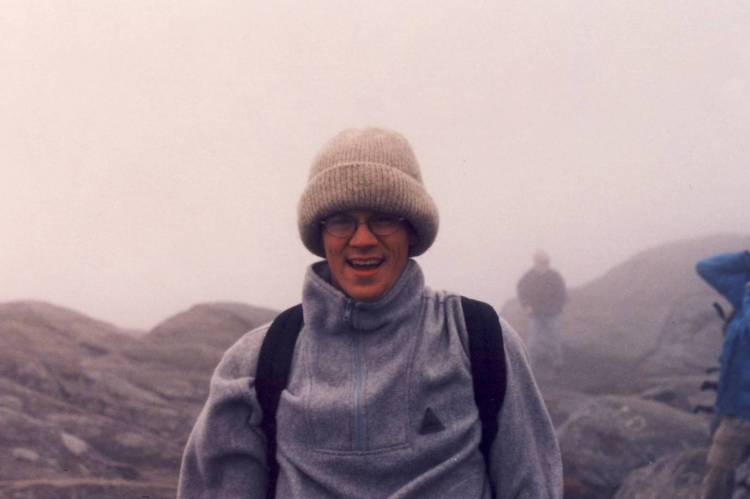

The last few hundred yards to the summit were hard-fought. We crouched and walked on all fours. We protected as well as possible all unprotected skin. The wind at the summit was incredible. I let my arms hang loose and marveled as they flapped like windsocks. I got my camera out of my pack.

When I got the film developed, I set the two pictures which had been taken at the summit side by side. I was touched by their similarity, by the fierce and happy grin of the wind-blown face which made me my father’s son.